Now that a reportedly “furious” (GB News), “angry” (Guardian) and “absolutely incandescent” (Express) Robespierre ‘Boris’ Johnson has been carted off to the tumbril by factions within the Covidian Republic who feel la Terreur of 2020-21 lacked the necessary psychopathic intensity and puritanical consistency, I thought it might be worth revisiting ‘Covid-19 and the infantilisation of dissent’ – a piece I originally wrote for the Daily Sceptic back in May 2021. It would of course have been just as easy for the media to describe the former Prime Minister as a longstanding parliamentarian who was “concerned” at, and “intellectually troubled” by, the weaponisation of the tempering mechanisms of parliamentary democracy for party political grudge-settling. Then again, live by an infantilised society, die by an infantilised society… Hands, face, space! Your mask protects me, my mask protects you! Thank you, NHS! #BorisIsALiar! #NeverKissedATory!! LOL!!! 😂 😂 😂 😀 😀

Emotion words. The role they were playing in the media/political response to the COVID-19 outbreak first became apparent to me on Monday 27th April, 2020. That was the day Boris Johnson returned to work following a period of convalescence from his COVID-19-related illness.

Speaking outside No. 10, he announced that he was (as his press team no doubt suggested he put it in order to resonate with the salaried classes) “back at his desk”. His statement contained all the usual Churchillian allusions. We were thanked for our “effort and sacrifice” and our “sheer grit and guts,” particularly in relation to “collectively shielding our NHS”.

Ultimately, though, strip away the rhetoric and what were we being given? A pretty bleak message. Continue staying at home, obey the lockdown and wait for the government to tell you when you can pick up whatever pieces remain of your lives, jobs, careers and companies. No sense of a timeline (however “phased”) for ending the lockdown; no sense of an ending to this period of unprecedented economic national self-harm; no sense of the certainty that our economy – and the people and businesses who make that economy tick – need in order to get back to generating the wealth and prosperity that publicly-funded institutions like “our NHS” need in order to do their job.

How should we “feel” about this? As a matter of fact, during his statement Johnson claimed already to know how we felt about it. “I ask you,” he said at one point, vamping the camera with the same type of nauseatingly faux sincerity that Tony Blair once made his calling card, “to contain your impatience.” Impatience. Did you know you were impatient? Personally, I thought I was “intensely sceptical of the government’s strategy” or “thinking about different ways to manage a pandemic”, or maybe even, in moments of self-aggrandisement, “intellectually dissenting”. Apparently not, however. Those of us who have done our best to research, read widely and think carefully about how it might be possible to, you know, defeat COVID-19 without ending up jobless, business-less and in rent or mortgage arrears, are apparently “impatient”.

One wonders how much of this type of thing British people will be able to stomach. Our economy is set to shrink by 13% this year, its deepest recession in three centuries. Public borrowing is set to surge to a post-WWII high. In the April-June period alone, economic output could plunge by 35%, with the unemployment rate more than doubling to 10%. At least 21,000 more firms went under in March 2020 compared with the same month last year – a year-on-year increase of 70 per cent.

Does any of this make you feel “impatient”? I’d imagine it might make you feel quite a few other things, most of them unprintable. But you will also undoubtedly be “thinking” quite a lot of things too. That’s the point from which this article jumps off.

Emotion words are dangerous things when it comes to democracy and democratic politics. The word “impatient”, for instance, suggests a tendency to be quickly irritated or provoked by something. It is, in that sense, the emotional response of the infantile and the immature (hence the common, everyday phrase, “impatient as a child”). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the neat rhetorical affordances of Boris Johnson’s phrase weren’t lost on those mainstream media types still fighting their last-ditch, tin-pot battles against Brexit or indeed any other social action that has even the slightest whiff of perceived nativism about it.

Thus, in the days following Boris Johnson’s first speech, we find the Guardian (of course) citing Fionnuala O’Connor approvingly (6th May) to the effect that, “[UK] Ministers of slim talent have bumbled through daily briefings and now big-business Conservative donors are impatient to reverse a shutdown so contrary to Brexiteer dreams”.

Elsewhere, the BBC’s Jenny Hill described Angela Merkel (6th May) emerging from a “stormy session with Germany’s regional leaders who were so impatient to restart their local economies that some had already announced plans to relax restrictions before the meeting even began”. Those leaders, Ms Hill noted with a condescendingly elitist nudge and a wink, “got their way and many Germans will no doubt be delighted at the prospect of beer gardens and Bundesliga”. Beer gardens and Bundesliga – such a wonderfully middle-class, Islington dinner party euphemism for “the AfD-fancying great unwashed”.

Meanwhile, the Guardian’s own entry into this impromptu “make lockdown critics stand in metonymically for nativists” competition (6th May) read as follows: “On Wednesday, chancellor Angela Merkel announced the latest gradual reopening of large shops, schools, nurseries, and even restaurants and bars – seemingly bowing to a growing impatience with lockdown restrictions that was manifesting itself in political pressure from the leaders of the 16 federal states, the mass tabloid Bild, and growing conspiracy theory-driven protests across major cities.” Lockdown critics: impatient, ill-educated… and also, it turns out, possibly unhinged too.

Of course, this is all to hang a lot of analytic weight off just one word. True enough. So it’s probably worth noting in passing that emotion words have proliferated elsewhere in media/political responses to COVID-19. Terrified, scared, anxious – all have recently been pressed into action within the public sphere. But here, let’s briefly consider the word “fearful”. Its implications of a purely emotional response to an external stimulus helps it perform much the same rhetorical work as “impatient”.

In his 10th May speech to the nation, for example, Boris Johnson was at it again, imputing certain emotions to his audience. “There are millions of people,” he declared, “who are both fearful of this terrible disease, and at the same time also fearful of what this long period of enforced inactivity will do to their livelihoods and their mental and physical wellbeing.” Again, did you know that you are fearful? And even if you did… is that all that you are? I would say that I’m “concerned” about what happens as the lockdown is phased out; that I’m “studying” all the available epidemiological/medical/scientific evidence to the best of my (admittedly limited) ability; and that I’m also “planning” for ways in which my business can respond to what will undoubtedly be a fluid, rocky and rapidly-evolving situation.

Concerned, studying, planning – these are action descriptions, not emotion words. True, they might be tinged with emotion, but fundamentally, deep down, each of these actions constitute a rational, cognitive response to an external stimulus. Indeed, they point to the type of cognitive work that individuals in any fully-functioning democracy need to undertake all the time – lockdown or no lockdown.

Does this imputation of certain types of feeling to the voters of the UK matter? I think it does. It was the American sociologist Arlie Hochschild who, in the 1980s, first argued that emotional cues may be among the most important cues in social interaction. Feelings, as we all know, are a kind of pre-script to action. That much is obvious. It is internal behaviour that we engage in that prepares us to act externally. In days gone by, you got angry (feeling) and then smashed things up (action); now, you get angry (feeling) and you engage in passive-aggressive social-media one-upmanship with your followers (action). There is, then, a clear link between how we feel and how we act.

But Hochschild went on to point out that in modern societies, there is much more to feeling than just some simple kind of inner authenticity. Her research into modern labour markets made clear that the feelings of individual employees were something that companies were increasingly seeking to own, and, in owning, control. People weren’t just buying an airline ticket anymore, they were buying the simpering smile of an airline hostess; similarly, people weren’t just buying a hamburger, they were buying a friendly encounter and the server’s cheery exhortation to “have a nice day now!” Employees were being (badly) paid as much for aligning their emotion management with the needs of their employer as they were for their physical labour.

In complex mass societies, governments also tend to put a surprisingly large amount of work into ensuring not only that the actions, but also the emotions, of the population are aligned with the norms and expectations that they’ve set across multiple different settings. Some of that is right and necessary, of course – we shouldn’t “hate” foreigners, just as children shouldn’t “trust” strangers and we should all feel “disgust” when we see prejudice in action. But what we also find is that modern government increasingly involves the repositioning of issues that would once have been seen as intellectual and cognitive issues as emotional phenomenon.

This matters to and for democracy. If something political like a society’s overall response to the threat of a pandemic is seen – as it should be seen – as an intellectual issue then it requires debate, argumentation, criticism and negotiation. In the end, of course, there might turn out to be arguments that are more workable, viable and plausible than others. But everything here depends on continuing debate, negotiation and compromise between equals.

On the other hand, if something political starts to be seen as an emotional issue, then there’s a definite tendency for the subsequent interaction to become laden with unequal power relations: the government and its appointed representatives announce a position or perspective, and then get to position everyone’s subsequent response on an emotional spectrum from usefully “docile” and “happy” to unhelpfully “immature”, “infantile” or, of course, “impatient”. Here, then, there’s only ever one argument which is workable and plausible (the government’s argument, of course) and a series of emotional responses to that argument which are either acceptable or unacceptable. In some ways, this is weirdly akin to a doctor-patient interaction on a psychiatric ward. Whatever you say to your Doctor, your words are never taken at face value, and only ever taken as the channel to some deeper emotional malaise that you yourself can’t see.

“I ask you to contain your impatience.”

“There are millions of people… who are both fearful of this terrible disease, and at the same time also fearful of what this long period of enforced inactivity will do to their livelihoods.”

These might seem like small, unimportant little snippets of what are, after all, “just” speeches. Indeed, it might seem like the real action, the big important stuff, is happening somewhere else. But when the Prime Minister of the UK imputes to the voting population feelings like “impatience” or “fearfulness” over something as important as the country’s response to COVID-19 it matters in deep, politically fundamental ways. His choice of words subtly starts to establish feeling rules for what should actually be issues of intellectual debate and discussion. We move from differing forms of cognition and argumentation to “good” and “bad” types of emotional response.

Happily clapping the NHS every week? Virtue-signalling one’s love for key workers on social media? Good emotion. Useful emotion. But we shouldn’t forget that it’s also politically docile emotion.

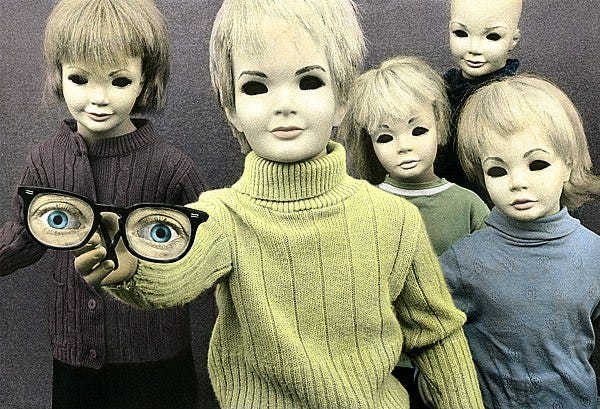

In the new political economy of emotion that Boris Johnson and others seem to be proposing, however, there’s also bad emotion. Here, a lot of us – lockdown sceptics in particular – no longer need to be listened to. We need to grow up. We’re not “sceptical” about the way in which the lockdown is continuing without any clear sense of an ending in sight; we haven’t “proposed” a dissenting virological or epidemiological viewpoint; we haven’t “deconstructed” elements of the computer code used to model the outbreak’s impact on society; we aren’t “advocating” for free speech in an era of unparalleled censorship; we’re not “intellectually opposed” to the idea of state power being wielded on this scale for such a prolonged period. In each and every case, we’re “impatient”. In this way, the dissent and debate that’s necessary to a fully functioning democracy is quietly repositioned at the end of the emotional spectrum marked as “infantile” and “immature”.

This is brilliant.